The original Paris needle-attack panic

Disturbing stories were circulating in Paris about a madman randomly assaulting young women in the street. His method of attack was bizarre: he would approach his victims from behind and poke them in the buttocks with a sharp instrument, probably a sewing needle attached to a walking cane, then run away – his perverse need apparently met with a single penetration. Though the flesh was pierced, sometimes deeply, the wounds received were not generally serious. What was unsettling about the assaults was the sense of violation experienced by the women and girls he targeted – that, and the fact that they were carried out in public, often in daylight hours; it created a feeling of intense vulnerability, as if no woman was safe on the street.

The police seemed baffled, unable to say whether one person was responsible or if it was a gang of men operating together. Within a few weeks, hundreds of similar incidents had been reported across France. Those responsible were given a name: les Piqueurs from the verb piquer, which translates as to prick, to jab, or to sting. “Piquer” in French is subject to the same double meaning as “to prick” is in English, and thus was the root of a great many jokes.

Like the killer clown craze of 2016, or today’s needle attacks in France and Britain, the culprits pursued vulnerable members of society and the way they went about it had a supernatural quality – striking in a crowd yet able to fade out of sight, seemingly able to multiply and appear in new places, making them impossible to capture in a conventional way.

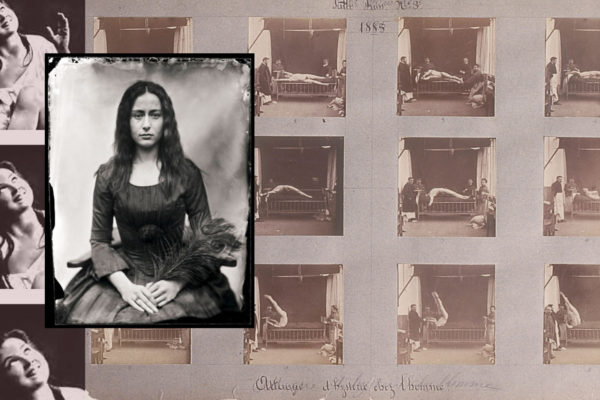

And like these recent panics, the needle crimes of 1819 generated masses of attention over a short period of time. Rumours were ramprant, copycat crimes flourished and conspiracy theories emerged, while bawdy cartoons and songs – the memes of the day – on the subject exploded. An intoxicating mixture of novelty, titilation and genuine alarm combined to create a moral panic that said a great deal about the the fears that society had about the anonymity of city life, and particularly how women moved through it.

Finally, a culprit was captured and convicted, the attacks petered out, and the collective hysteria passed. And yet how much of it was real?

The spread of attacks and panic

The first press mention of women being attacked by a mysterious “piquer” was in December 1819, in a statement issued by the police. It spoke of an individual who took “cruel pleasure” in approaching women from behind and pricking their buttocks through their clothes with a sewing needle attached to the end of a walking cane or umbrella. What’s more, it specified that the “maniac” seemed to target young people who were “naturally modest”, whose education and upbringing prevented them from making a fuss in the moment, thus allowing the perpretator to get away.

If the intention of the police in making this statement was to reassure the public that such incidents were being taken seriously, then it was a failure. Instead, people grew immediately more alarmed. Press stories detailing new crimes appeared daily. The locations of the attacks read like a guide book to Paris: women were attacked in in the jardins des Tuileries, on the Pont-Neuf, near the Palais-Royal, at the Louvre. And the crimes were audacious. One report tells of a woman who was pricked outside her front door, another while was walking arm-in-arm with her husband at the time. Nowhere – and no one – was safe. Though women and girls were overwhelming the victims, even men were falling victim to the Piqueurs. One young man was attacked while buying a ticket at the theatre, another was “dangerously ill” after being jabbed in the street. By the time the needle panic was over, police had received reports of over 400 needle attacks.

And the attacks were spreading. Before long, police in Lyon, Bordeaux, Calais, Marseille and Lille would be investigating similar crimes. This geographical diversity proved one thing that the Paris police and press had suspected for some time: that there was more than one person behind the incidents. Copycat crimes are nothing new and the excitement generated by the Paris needle attacks had proved too much for the weak-willed, desperate kind of personality that follows a criminal trend. At the lighter end of the scale, three schoolboys “from honest families” found themselves in a Brussels prison at Christmas after being caught poking a woman with a needle stuck to the end of a stick.

Poisoned needles

As rumours of new attacks abounded, the severity of injuries sustained increasing with each retelling. In a newspaper letters page (L’Indépendent, 20 December 1819), an anonymous writer tells how he had believed that the Piqueur attacks were reducing in frequency – and he had been on the point of allowing his wife to leave the house again – when a neighbouring woman, a midwife, was attacked at 5 pm. The weapon pierced her woollen skirt and penetrated 2.5 cm deep into her thigh. She sufferered swelling, vomiting and weakness during the night that followed.

The midwife’s symptoms, along with fainting and fevers, were being reported by other victims, too. This kind of reaction wasn’t in keeping with a simple skin prick, it suggested that there was something more sinister afoot. Were the Piqueurs dipping their needles in a toxic substance, poisoning their victims now? It was one thing for the Piqueurs to induce a brief pain and loss of dignity with a needle prick, but entirely another to inflict actual bodily harm on their victims. Word on the street was growing more frantic, less in touch with reality. In Normandy, a man wrongly identified as a Piqueur, had to be saved from a crowd that was ready to lynch him.

With tensions this high, it wasn’t long before deaths were falsely attributed to the Piqueurs. One case involved a vet’s daughter who was rumoured to have died following an attack by a Piqueur; not only was this untrue, she was found to have died of natural causes six week before the attack was supposed to have taken place.

Conspiracy and cynicism, marketing and memes

Not everyone falls victim to social hysteria at a time like this. Certain maintain a healthy sense of doubt about the nature and scale of the root problem; while others take this sceptiscism to an opposite extreme. This latter standpoint was the case for some conservatives. A Royalist newspaper, Le Drapeau Blanc, printed the conspiracy theory that the needle attacks weren’t real, they were fabricated by the police purely to distract the public from the debates being carried out by the government. Lower down the scale were those who expressed doubt over the verity of some of the women’s statements. Were they imagining, or exaggerating a crime? Did these young women just want the attention of being part of a national scandal? Without a man to back up an account of a violation, it was difficult for some men to believe a woman’s account of what had happened.

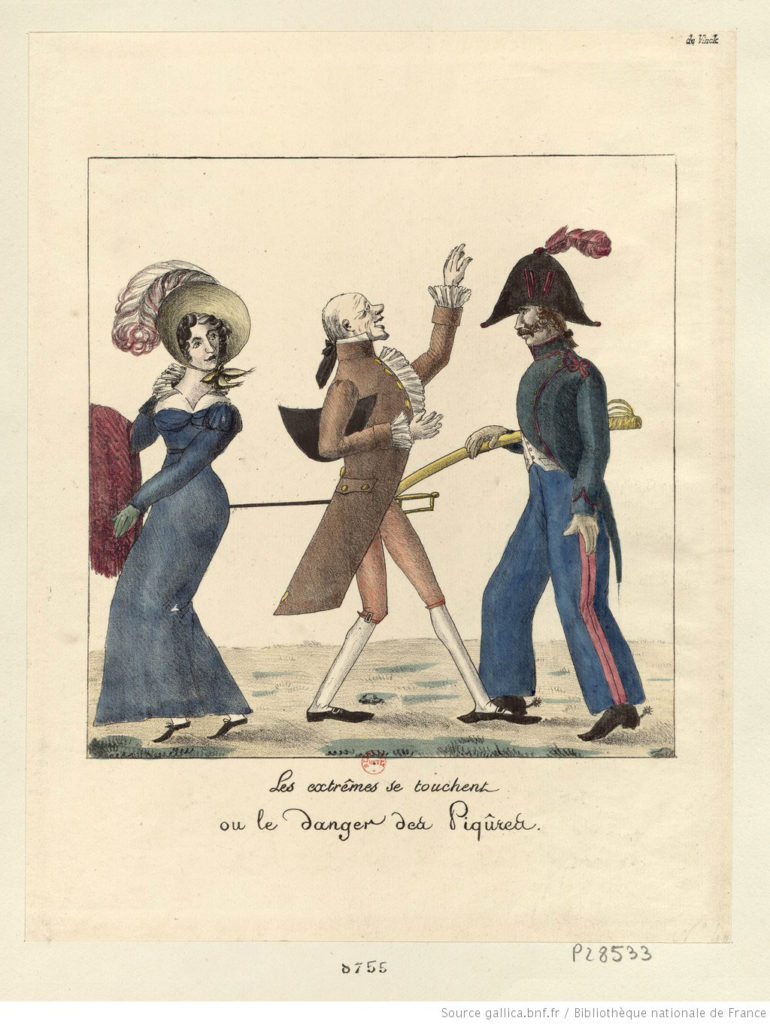

Then there were those who found it all funny. The crime itself was in that sweet spot of being sufficiently serious to cause alarm, but without any actual danger to life. It also involved penetrating an intimate part of a woman’s body, something that was ripe for comedy. The “prick” gags were aplenty, as can be seen in the periodical illustrations from the time.

In this first drawing, we see a heavily pregnant woman with the caption, “The result of a pricking” (Le résultat d’une piqueur), while another woman runs away from a penis-shaped instrument in the background.

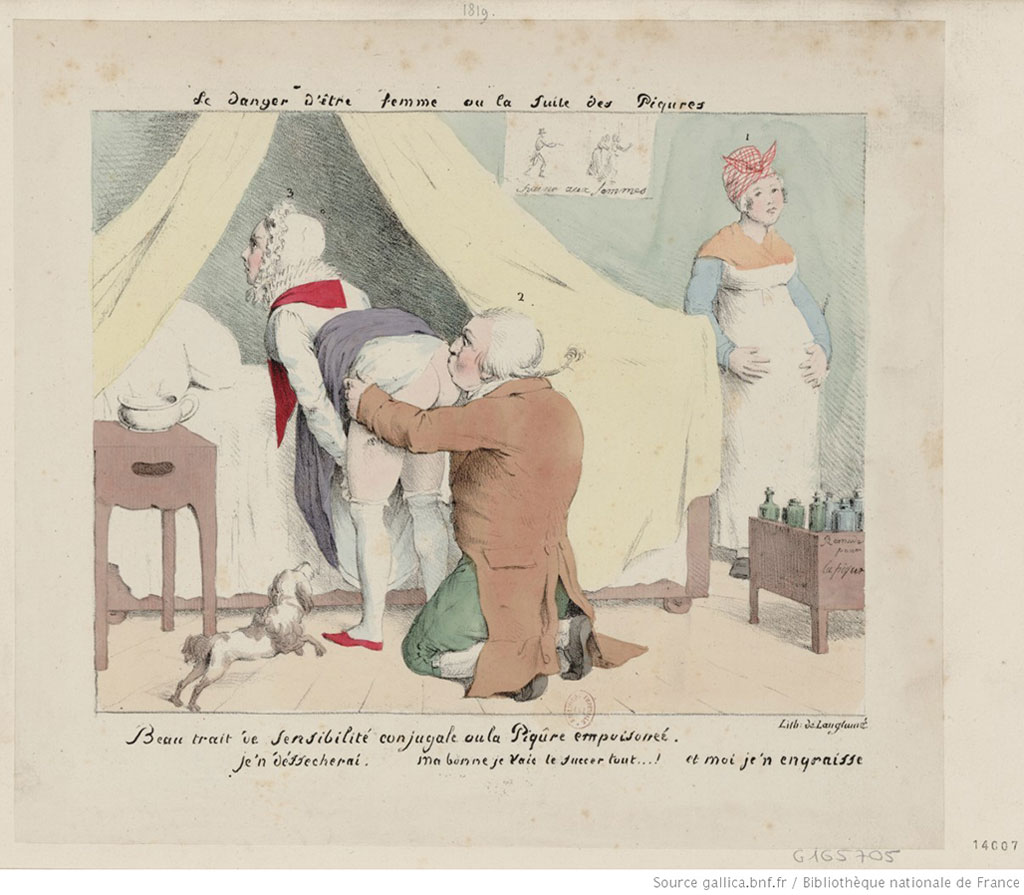

In this next, more explicit drawing titled “The danger of being a woman or the result of prickings”, a husband helps his wife by sucking the poison out of the site of the pricking, i.e. her buttock. He says, “My darling, I’ll suck it all out… And I’ll get fat!” In the background, their pregnant maid (the result of another prick attack) watches on.

One other detail worth noticing in the above illustration is the chest of bottles, evidently there to aid the wife’s recovery after being pricked. These aren’t there without reason. A pharmacist in the Marais district of Paris attempted to capitalise on the public’s fear by concocting and advertising a lotion said to be an antidote to the pricks. While this kind of quackery is to be expected, humourists took it one step further by imagining other products that could sold to women to protect them – notably bum guards.

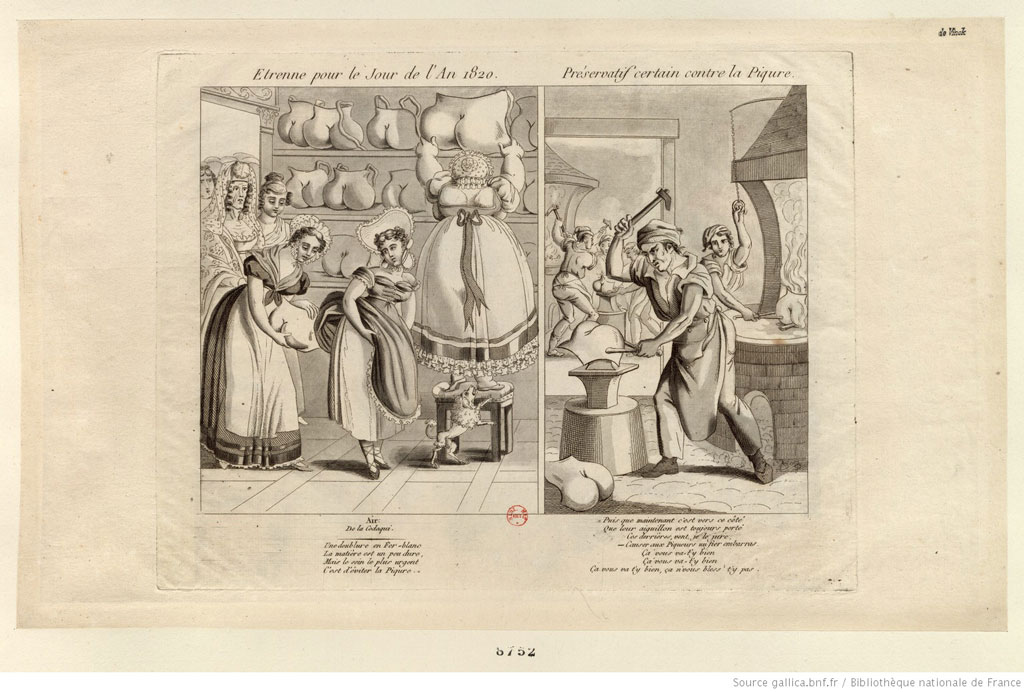

These two illustrations show “Preparations for New Year’s Day 1820”. In the first, a woman, helped by a shop assistant, tries on a buttock-shaped plate to be worn on top of her actual behind. We see all kinds of shapes and sizes of bum guards on the shop’s shelves and a queue of customers waiting to get in. In the background, an overweight woman takes down a comically large bum guard from the shelf. The second shows the manufacturing of the bum guards in a blacksmith’s forge – they’re making literal buns of steel.

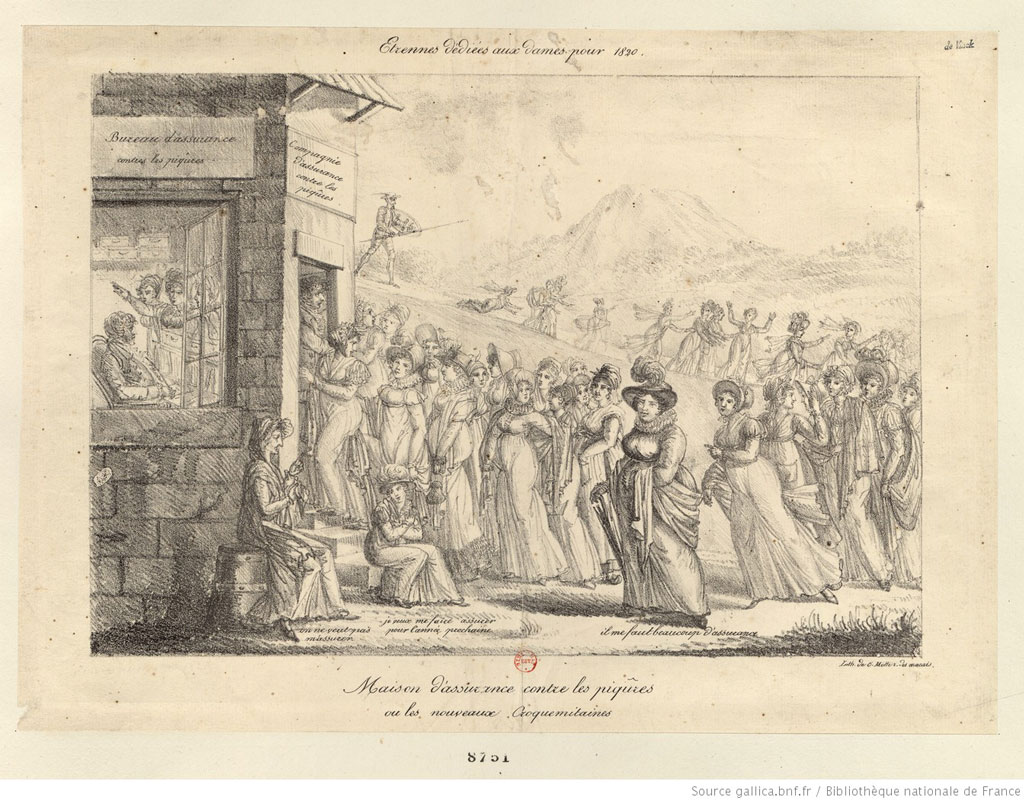

Finally, this (below) drawing covers a similar theme, in a slightly more high-browed, yet nastier, and definitely less funny way. Again, these women are preparing for New Year but this time it’s insurance they’re looking for. A long queue of attractive, buxom women wait to sign up for “anti-prick insurance”. Those at the back of the queue stumble while fleeing from a man in medieval armour holding a shield and terrifying-looking spear. In the foreground, there are three women: to the left is an “ugly” woman who says she doesn’t need insurance; in the middle is a younger woman who says she needs insurance next year; to the right is an overweight woman saying she needs lots of insurance. The message is clear: women can either be sexy and scared, or unattractive and the subject of mockery. The men depicted are either violent or making money off the women’s fears – an equally false opposition.

The bubble bursts

It couldn’t last. The beginning of the end came in January 1820 when Auguste-Marie Bizeul (35), a tailor from Paris, was found guilty of pricking three fouteen-year-old girls with needles in August of the previous year. He was fined 500 francs and sentenced to five years in prison. During the trial, two of the girls told how they were walking together in the street when they passed a man with his hand wrapped in a black silk handkerchief. Each felt a stinging sensation in their buttocks as he walked past them. They encountered the man shortly afterwards in another street and the same thing happened again. A third girl from the same area testified to having experienced something similar with a man they were all later able to identify as Bizuel. None of the girls reported the incident at the time out of embarrassment; they were only persuaded to do so later when news of the other Piqueur attacks came out.

The head of the Paris Surêté (the police’s detective division) at the time was the Eugène Vidocq, a pioneering criminologist, one-time convict and world-renowned detective – but one that wasn’t above taking shortcuts to solve cases. The hasty trial, the dearth of evidence, the convenience of a tailor being found responsible in attacks that involve sewing needles left many doubting the solidity of the conviction.

What can be said, however, is that the panic bubble seemed to have been lanced. While attacks continued for a time afterwards, the fervour with which they were reported, or consumed by the public was far less intense than previously. There would be other spates of needle attack in the years that followed but, like the classic second album, they didn’t have the same appeal as the first ones. The novelty had worn off.

Sources

La légende urbaine des “piqueurs de fesses”, Pierre Ancery, Retro News

L’ODIEUX “PIQUEUR DE FESSES” QUI TERRORISAIT LES PARISIENNES, Cyrielle Didier, ZigZagParis

The History of an Urban Fear: Attacks by Piqueurs on Women in Restoration France, Emmanuel Fureix, published in Revue d’histoire moderne & contemporaine (translated into English)

Photos

Main photo by Henry Lai on Unsplash

All other images are from gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France